Monthly Journal

March 2025

International Press Review

The most relevant events of the area through international sources

Trump postpones sanctions against energy giant NIS for another 30 days

Reuters

The Trump administration extended the sanctions waiver of Serbian oil company NIS for a second 30-day period. Without the waiver, crude supply cuts could have harmed NIS, which operates Serbia’s sole oil refinery and supplies the majority of the country’s fuel needs. NIS imports 80% of its oil through Croatia’s Janaf pipeline, with the rest coming from domestic production. NIS is primarily owned by Russia’s Gazprom Neft and Gazprom. The United States initially imposed sanctions on Russia’s oil sector in January, giving Gazprom Neft 45 days to withdraw from NIS. A previous 30-day extension was granted in February. To mitigate sanctions, Gazprom Neft transferred 5,15% of its stake in NIS to Gazprom, reducing its majority control.

Serbia proceeds towards building an oil pipeline to Hungary

SeeNews

Serbia’s government has approved a spatial plan for a 113-kilometer oil pipeline linking Hungary, with the goal of diversifying its energy supply. The underground pipeline will connect Horgos on the Hungarian border to Transnafta’s oil terminal in Novi Sad. It will have an annual capacity of 5,5 million tonnes. The flow will depend on Serbia’s needs and oil availability via Croatia’s Janaf pipeline. Serbia and Hungary signed the pipeline agreement in June 2023. Eventually, the pipeline will extend over 300 km, linking Novi Sad to the Druzhba pipeline’s receiving station in Szazhalombatta, in Hungary.

Kenya last country to recognizes Kosovo

Prishtina Insight

Kenya officially recognised Kosovo as an independent and sovereign state in March, marking the first diplomatic recognition for Pristina in four years. The announcement was made by Kosovo’s former President Behgjet Pacolli, who has long lobbied for recognition, and later confirmed by current President Vjosa Osmani. Pacolli described the recognition as a significant diplomatic achievement. He highlighted his ongoing efforts since 2009 to secure Kenya’s recognition, while Osmani welcomed the decision, calling it a breakthrough in Kosovo’s global recognition efforts.

PM Kurti announces massive investments in defence

Hashtag.al

Kosovo Prime Minister Albin Kurti announced that his government will allocate over one billion euros to strengthen the Kosovo defence forces during its future new mandate. Speaking at a government meeting, he highlighted plans to triple the defence budget, increase investments in armaments, and develop a domestic military drone and ammunition factory. Kurti’s party, Vetevendosje, won the February elections with around 42% of the vote but has yet to formalise a governing coalition.

Albania, Croatia and Kosovo sign memorandum on military cooperation

European Western Balkans

Albania, Croatia, and Kosovo signed a joint defence cooperation declaration aimed at strengthening the defence industry, improving military interoperability, countering hybrid threats, and supporting Euro-Atlantic integration. Serbia condemned the move, viewing it as a threat to its territorial integrity and regional stability. Albanian and Croatian defence ministers emphasised the importance of unity in the face of security challenges, while Kosovo’s Minister of Defence clarified that the memorandum was not intended to threaten anyone, but to ensure regional stability. Serbian officials, however, denounced the agreement, calling it provocative and destabilising.

OSCE concerned about the ongoing crisis in Bosnia and Herzegovina

Reuters

Elina Valtonen, chairperson of the Organisation for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE), has urged Bosnian leaders to respect the constitutional order and engage in dialogue to resolve the ongoing political crisis. Valtonen expressed deep concern during her visit to Bosnia and Herzegovina, which is experiencing its worst political turmoil since the 1990s war. The crisis centres around Milorad Dodik, the president of the Serb Republic (Republika Srpska), who defied rulings from the international peace envoy Christian Schmidt. This has sparked a dispute between Dodik, supported by Russia and Serbia, and the Western powers, exacerbated by Dodik’s conviction and ban from public offices.

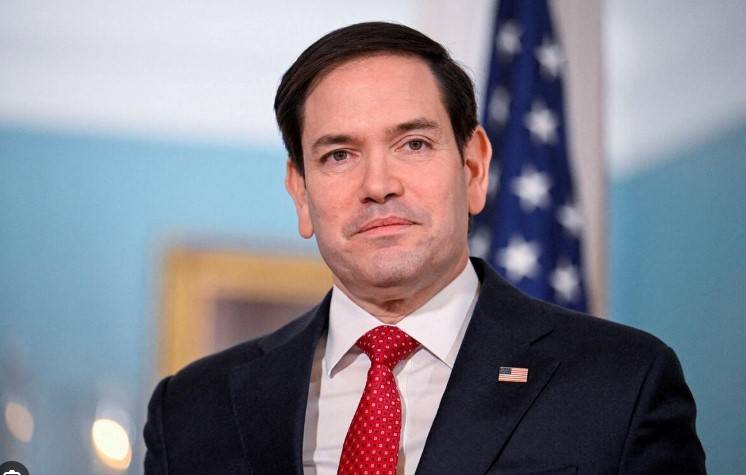

Washington to work for preventing separatism in Bosnia

AFP

US Secretary of State Marco Rubio emphasised that Washington is committed to preventing the breakup of Bosnia and is considering additional pressure on Bosnian Serb leaders to counter their separatist policies. Rubio stressed the importance of avoiding another conflict in Europe and stated that the USA were reviewing their options to address the situation. The crisis escalated when Bosnian Serb leader Milorad Dodik defied the international peace overseer and restricted federal police and judiciary access to Republika Srpska. Rubio’s stance aligns with NATO and European allies.

Riots erupt in Romania after pro-Russian candidate is banned from elections

CNN

Romania’s electoral bureau barred far-right and pro-Russian presidential frontrunner Calin Georgescu from running in May’s election, citing his failure to comply with electoral regulations. The decision triggered violent protests in Bucharest, with Georgescu’s supporters clashing with security forces. The ruling came shortly after prosecutors launched a criminal investigation into Georgescu for attempting to subvert the constitutional order and establishing a fascist organisation. His actions, including a potential Nazi salute, similar to the Musk’s one, sparked further controversy.

Vucic to travel to Russia on 9 May

AFP

Serbian President Aleksandar Vucic confirmed he will visit Moscow in May for the World War II victory commemorations, marking his first trip to Russia since the invasion of Ukraine. Vucic accepted an invitation from Russian President Vladimir Putin to attend the 80th anniversary of the liberation from Fascism at Red Square. Despite being an EU candidate since 2012, Serbia maintains close political and economic ties with Moscow. Brussels has repeatedly urged Serbia to align its foreign policy with Europe.

Macedonians pessimistic about EU integration

Telegrafi

A survey by the Institute for Political Research show found that over 61% of North Macedonian citizens had supported the EU referendum, while 23,5% opposed it. Support was highest among ethnic-Albanian respondents at over 77%, compared to 55% among Macedonians. Nearly 30% believed that North Macedonia would never join the EU, and only 20% thought membership could occur within five years. Just 26% felt that recent reforms had advanced European standards.

Slovenia considers creating a consortium for weapon production

STA

Slovenian Sovereign Holding (SSH) is rumoured to be in talks with Slovenian defence company Valhalla Turrets and with the German giant Rheinmetall about establishing a major weapons system manufacturer in Slovenia. Milos Milosavljevic, director of Valhalla Turrets, confirmed that discussions are ongoing, stressing that state support would be crucial for such a large-scale project. SSH has not confirmed the talks, citing legal restrictions on disclosing details about state capital investments.

The Insight Angle

Srdjan Majstorovic

Srdjan Majstorovic is currently the Chairman of the Governing Board of the think tank European Policy Centre (CEP). He previously worked as the Deputy Director of the Serbian European Integration Office and as a member of the Negotiating Team for the Republic of Serbia’s Accession to the European Union, where he was in charge of political criteria and rule of law chapters. He is also a member of the Balkans in Europe Policy Advisory Group (BIEPAG).

Serbia is currently experiencing the largest and longest protests in its recent history. Are you surprised by the size of this movement and the fact that young people and students are at the helm?

For years, the citizens of Serbia have lived in a political system that is defined as a captured state. The state has been captured by the ruling party, undermining democratic institutions and establishing control over the security services, the media and the management of the economy.

The collapse of the canopy at the Novi Sad railway station and the death of 16 innocent victims has fully demonstrated the tragic consequences of deep-rooted corruption in Serbia and the fragility of the “stabilocracy”. In these circumstances, the majority of citizens of Serbia decided to oppose the status quo and fight for justice and democracy. Students took the lead in these protests, and this was a surprise at first. But with their non-violent methods of protest, witty and carefully planned actions, they played the role of avant-garde, freeing the vast majority of Serbian citizens from fear and motivating them to join the common fight for democracy and rule of law. These protests also represent a generational movement. This generation has made it clear that they will either succeed in their struggle for creating better Serbia or Serbia will be left without its youth, who will leave it in search of a better life.

Despite the ongoing protests the authorities in power appear either unwilling or unable to meet the students’ demands. How do you see the situation unfolding? Is there a risk of violence or serious destabilisation in the country?

The incumbent government is unable to meet the very clear demands of the students because it would mean the end of this regime. The students demand strict respect for the principles of the rule of law and punishment of the perpetrators who physically attacked them, most of whom are members of or close to the ruling party.

One of the key events thus far was the protest in Belgrade on 15th of March, which was the largest public protest in the modern history of Serbia (250-350.000 people). During the 15-minute silence to honour the victims, an unknown sonic device was activated, which led to panic and a catastrophe was avoided by mere chance. State representatives denied responsibility, while independent experts indicate that Serbian security forces possess this type of weaponry even though it is illegal by law. This and other similar indicators are showing that the regime is ready for an escalation of violence. Whether this will happen depends on the resilience of students and citizens in protest, their ability to cooperate and articulate their demands in policy proposals on how to resolve the crises, but also on the interest of the international community concerning the situation in Serbia.

The European Union—and the West more broadly—seem rather reluctant to engage with the crisis unfolding in Serbia. Do you agree with this assessment? If so, why? And what consequences could this have for Serbia’s European aspirations?

The reluctance to previously engage with Serbia was due to numerous factors: geopolitical, given the war in Ukraine and its consequences in Europe; economic, given the Serbian president’s lucrative transactions with EU Member States governments; outstanding regional issues, where Serbia plays significant role such as dialogue with Kosovo, and also EU’s need for rare minerals such as lithium from Serbia. The president of Serbia was recently visiting the presidents of the European Council and European Commission and the messages sent by the EU officials did not deviate from the usual Brussels-diplomatic style and language that is characteristic for such meetings. However, the momentum, context and way these statements were published speaks volumes. This time there were no joint statements or tasteless and unnecessary outpourings of intimacy by EU officials towards the President, which in the past had a major impact on the decline of Serbian citizens’ trust in the EU and its credibility. It is significant that both EU officials emphasised the need for the Serbian leadership to focus on topics that are essential for democracy in Serbia, such as free media, the fight against corruption and the need to change electoral conditions. Why was it not done before? Well, now we have hundreds of thousands of people on the streets of Serbian cities clearly demonstrating they are ready to fight for democracy, with or without EU’s support.

Meanwhile, Bosnia and Herzegovina is also facing a deep crisis with the Bosnian Serb leadership openly antagonising the central government, while North Macedonia is in turmoil following the horrific incident in Kocani. After Serbia, is it possible that we will see a broader destabilization across the Balkans?

We must be careful with the terms that are characteristic of the stabilocrats. The fight for justice and democracy is not necessarily destabilizing Serbia or region. If political changes occur in Serbia, there is a chance that the rest of the region will also become safer, more predictable and more stable. The current security situation is indeed not favourable. It is to some extent a consequence of the unsuccessful policy of EU enlargement to the Western Balkans.

Since the beginning of the Russian aggression against Ukraine, the EU has been talking about strategic enlargement, as if this was not evident 3, 4, 10 years ago. It is very clear that the EU and the Western Balkan countries (and the candidates from Eastern Europe) must recognize a common interest in the unification of Europe. Not just any unification, but one based on the principles of democracy. This means that the EU must prepare for the acceptance of new members in organizational, functional, value and financial terms, and resolve its own internal issues.

On the other hand, the candidates must be much more determined to show with concrete steps that they sincerely want to adapt to the conditions for accession to the Union. For this, we need a joint plan, with activities, obligations, resources, roles and deadlines. As long as this is not the case, the story of EU enlargement will not be credible enough and will provide an excuse for the political elite in Serbia to continue their populist practice which is taking us all further away from the common goal.

The Key Story

Strategic trends

The social and political crisis in Serbia intensifies, with no signs of stabilization in sight

Serbia is still experiencing the largest and longest protests in recent history, with no signs that the current political and social crisis will be resolved. This leaves room for additional, potentially dangerous destabilization or even violence.

The crisis, sparked by the collapse of a canopy at Novi Sad railway station that killed 16 people in November 2024, peaked on the 15th of March in Belgrade, Serbia’s capital, with a massive student-led rally. More than 300.000 people were estimated to have participated in the protest, the largest turnout since a deadly roof collapse at a railway station last year sparked a national protest campaign.

For months, student-led protesters have organized protests across the country, staging rallies in Serbia’s major cities, but also taking their anti-corruption campaign to rural areas and small towns, which have long formed the backbone of President Aleksandar Vucic’s support. The students’ “return” to Belgrade on 15 March further intensified the growing pressure on Vučić’s rule, which had already seen several high-ranking officials, including the prime minister, resign in recent months. The Belgrade demonstration, which was likely the largest since those against the Milosevic regime, drew a diverse cross-section of society, including war veterans, and brought together people from both the far left and right.

Pro-government students and supporters of Vucic, ultranationalists, militia members, and alleged football hooligans also gathered in the capital to form barricades near the parliament building before the 15th of March, according to analysts and critics of Vucic, a dangerous move organised by the elites in power. This raised concerns about a possible clash with student-led demonstrators who planned to march past Parliament later on Saturday. During the protest, riot police were stationed in layers around the encampment and the parliament building, and analysts and experts warned that the situation could quickly escalate.

While no clashes were reported during the protest, there was a serious and very dangerous incident during the Novi Sad victims’ silence. At around 19:00, thousands of peaceful protesters scattered in one of the streets in central Belgrade, abruptly, without any reason. The students subsequently accused the authorities of using against them a kind of “sonic cannon,” a long-range acoustic device that experts claim is illegal. Videos of the moment the device was allegedly activated, causing the crowd to disperse, circulated widely on social media, with viewers shocked by disturbing footage showing the crowd suddenly dispersing in a downtown street. Hundreds of witnesses described a sound resembling a passing plane or an approaching train, which caused significant distress, panic, and some minor injuries.

Serbian politicians and police have repeatedly denied using a “sonic cannon” against protesters during the weekend’s massive anti-corruption rally in Belgrade. However, Interior Minister Ivica Dacic confirmed later that the police possessed such equipment but denied its use against protesters. Serbian authorities announced an investigation and requested assistance from the US FBI and Russia’s FSB, reflecting Serbia’s close ties with Russia despite its EU candidate status.

The alleged use of the sonic cannon, combined with the presence of pro-government counter-demonstrators in Belgrade, raised the risk of violence during Serbia’s protests. The authorities also began using more inflammatory language when referring to the protest. Government-backed media spread claims of a planned “coup” organised by the opposition, while Vucic accused demonstrators of plotting “large-scale violence”. The president also stated that he would not succumb a “Maidan-like” pressure, referencing Ukraine’s 2014 protests that ousted its pro-Kremlin leader.

Meanwhile, the ongoing political crisis showed no signs of resolution, further deepening tensions across the country. While students remained resolute in their demands, vowing to continue protesting until their requests were met, Vucic repeatedly put forward two options to resolve the crisis—both of which were strongly opposed by the opposition and the protesters. His proposals included either early elections or the formation of a new government backed by the ruling Progressive Party and the Socialists. Vucic, on the other side, firmly rejected any possibility of establishing a transitional government, a key demand of both the demonstrators and opposition leaders.

Against this backdrop, Serbia appeared to be heading for weeks of continued unrest, with tensions visibly escalating and the risk of further destabilisation growing by the day.

Further News and Views

Bosnia requests an international arrest warrant for Dodik

Sources: Deutsche Welle, Anadolu, Balkan Insight

A court in Bosnia requested to the Interpol an international arrest warrant for Milorad Dodik, leader of the Serb-majority Republika Srpska, accusing him of undermining the post-war order established in 1995 and of attacking the Constitution.

Dodik was recently sentenced to one year in prison and barred from office for six years for defying the decisions and the authority of Christian Schmidt, the international envoy charged with overseeing the peace deal that ended Bosnia’s inter-ethnic war in the 1990s. Last month, as a reaction to his judgement, Dodik attempted to bar Bosnia’s central police from operating in Republika Srpska, a move later overturned by the Constitutional Court. Dodik and his allies refuse to recognise Bosnia’s prosecution office and reject calls for questioning in Sarajevo. Meanwhile, tensions in the country continue to rise.

A pro-Russia nationalist, Dodik has repeatedly threatened to secede from Bosnia and Herzegovina, jeopardising the Dayton Accords, which ended the Yugoslav Wars and established the country’s two governing entities: the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina and Republika Srpska.

In March, a Bosnian court issued a domestic arrest warrant for Dodik and two Republika Srpska officials, accusing them of attacking the constitutional order. However, Dodik defied the order, travelling to Serbia and then to Israel. The court cited his movements as justification for international action, placing the matter in Interpol’s hands. Interpol still did not reply to the request, while Dodik travelled to Moscow to meet Putin at the end of March.

Anger and protests in North Macedonia after tragedy at music club

Sources: Al Jazeera, AP, BBC

North Macedonia witnessed a period of mourning and anger in March, following a devastating nightclub fire in Kocani that claimed 59 young lives and left hundreds injured. The blaze erupted during a concert when flares ignited the ceiling, rapidly spreading through the overcrowded venue.

Authorities arrested 20 individuals, including officials and the nightclub manager, as allegations of corruption and safety violations emerged. Investigations revealed severe breaches of fire regulations, including the absence of emergency exits, fire extinguishers, and other essential safety measures. In response, the government ordered nationwide inspections of entertainment venues.

Public outrage grew as citizens and students gathered for memorials in Skopje and Kocani, condemning alleged systemic negligence. Thousands of protesters, in particular students, later marched through Skopje, demanding accountability, marching near government offices and applauding medical staff for their response to the tragedy.

The fire, which broke out on the 16th of March during an indoor pyrotechnics display, underscored failures in regulatory enforcement, according to critics. The Macedonian Prime Minister, Hristijan Mickoski, acknowledged public anger but dismissed criticism from political opponents, accusing them of exploiting the tragedy.

EU - NATO

NATO’s Rutte focusing on the situation in the Balkans

Sources: Kosovo Online, BNE Intellinews, B92, NATO

NATO Secretary General Mark Rutte visited the Balkans to address the region’s precarious situation and to show determination in maintaining peace and stability. In March, he spoke with leaders from Serbia and Kosovo, urging dialogue and the normalization of bilateral relations. In Kosovo, Rutte reaffirmed NATO’s support for the normalization of relations between Belgrade and Pristina, emphasizing the need for both parties to make “appropriate compromises” in the EU-mediated dialogue. Rutte also travelled to Bosnia and Herzegovina, where he emphasised NATO’s commitment to the country’s stability, sovereignty, territorial integrity and security. He stressed the importance of upholding the Dayton Peace Agreement, warning that actions undermining it posed a direct threat to Bosnia’s security. Serbian President Aleksandar Vucic reported a productive phone discussion with Rutte, focussing on Serbia-NATO relations and the broader Western Balkans situation. Rutte also emphasized the importance of continued cooperation to support stability in the region, including through NATO’s partnership with Serbia.

ECONOMICS

China might sue Serbia for delays in the construction of a power plant

Source: Serbia Business Forum, Global Arbitration Review, NIN

Serbia is facing a potential arbitration battle with China that could strain its close ties with Beijing over the Kostolac B3 Thermal Power Plant. China Machinery Engineering Corporation (CMEC) sought 795 million dollars in international arbitration, citing inflation, the COVID-19 pandemic, the Ukraine war, and project modifications by Serbia’s Electric Power Company (EPS) as reasons for the four-year delay, local media in Serbia claimed. In response, EPS and the Serbian state are planning a counterclaim for losses from electricity imports. Originally set for completion in 2019, the project was repeatedly delayed, concluding only in December 2024. After failing to renegotiate the contract price in Serbia, CMEC escalated demands to Belgrade in June 2024, with its president warning of arbitration. If CMEC prevailed, the total project cost could reach 1,5 billion dollars, raising concerns over the implications of Serbia’s 2009 intergovernmental agreement with China.

Stefano Giantin

Journalist based in the Balkans since 2005, he covers Central- and Eastern Europe for a wide range of media outlets, including the Italian national news agency ANSA, and the dailies La Stampa and Il Piccolo.