The contemporary hybrid media system (an idiom coined by Andrew Chadwick) is reshaping the infosphere in a never-seen-before fashion, allowing new ways and means not only of communicating and informing, but also of running large-scale influence operations with concrete risks and real impacts.

In this sense, the digital ecosystem offers polarising actors the ideal environment to carry out micro-targeted INFO OPS, election interferences, and disinformation campaigns, in an effort to sow division within Western democracies and in some cases undermine NATO, the EU and international organisations’ credibility.

Furthermore, in the near future Artificial Intelligence and its disruptive applications (spanning from AI-enabled disinformation attacks, to automated behavioural microtargeting, and deepfake synthetic media) will likely make hostile influence operations more precise, complex, and unpredictable.

From a NATO perspective these manipulations can be carried out at any level, including in first instance the Alliance’s level. As illustrated by Jakub Kalensky in his contribution to Game Changers 2020 Dossier, NATO and Allied countries’ adversaries within the infosphere, like Russia, are promptly adapting their operations to exploit fault lines in order to subtly undermine trust towards the Organization as well as its credibility.

Coordinated disinformation campaigns carried out against the Alliance in the Baltics and Poland (including the long-standing Information Operation Ghostwriter) are just the latest, more visible examples of the phenomenon.

As Daniel Sunter recently reported, since 2014 the Western Balkans have increasingly become the theatre of anti-NATO and anti-West malign information activities in Bosnia and Herzegovina, Montenegro and Serbia.

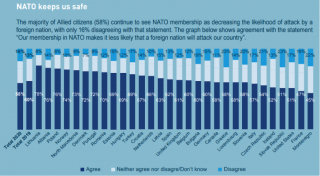

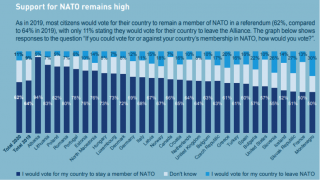

In this respect, looking at NATO Secretary General Annual Report 2020, it is noteworthy that Montenegrins’ moderate level of support towards the Alliance registered by polls (the lowest among all Allies, see charts below) offers the ideal frame in which anti-West narratives can gain traction.

Second, the Allied countries’ domestic political sphere. On digital platforms and social media, radicalised individuals gather in fringe violent groups, pivoted around anti-democratic sentiments, conspiracy theories and extremist ideologies, triggered by disinformation and polarizing narratives.

The Capitol Hill Riot represents a convincing example of how divisive rhetoric may lead to massive implications and risks for democratic institutions, national security and stability.

Third, the societal level. The running infodemic surrounding COVID-19 outbreak is not limited to conspiracies or false political rumours. As argued in a study published in the American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene and reported by the BBC, in the first three months of 2020 more than 800 people may have died and about 5.780 people were admitted to hospital around the world, as a result of medical misinformation on social media. The border between wilful disinformation and unintentional misinformation is particularly hazy especially if one keeps in mind that also powerful economic interests enter the fray.

Moreover, it has been scientifically demonstrated that the spread of false information suddenly erupts in correspondence with major crisis situations and natural disasters, with the potential to sharpen citizens’ fears and anxiety and hamper effective crisis management by governments and institutions, like e.g. the Euro–Atlantic Disaster Response Coordination Centre.

This dangerous environment requires an adequate response: while the Alliance is devoting great efforts to ensure clear, effective, fact-based information to its own public, it should also strive to study, analyse, and understand the adversaries’ target audience in the unfolding battle of narratives.

Taking stock of which social groups are more prone to destructive narratives, what are their values, what the interests at stake, and what their view of social order is can be a crucial knowledge when trying to engage with these audiences. Not all audiences can be engaged by the Alliance due to clear institutional constraints, but NATO’s response should always keep in mind what American pollster Dr Frank Luntz stresses, “It’s not what you say, it’s what people hear” — or better, are inclined to hear.

From the Allied countries’ point of view, a further point may be the creation of permanent national task forces. Currently, different centres and projects led by the EU and NATO (e.g. EUvsDisinfo, Hybrid CoE, StratCom CoE) exist, but their reach is still limited and in some cases they should be streamlined.

These task forces have the essential mission to create a consolidated expertise and an elite capability in complex information operations.

Finally, fostering digital resilience of societies requires broad, easily-accessible and quality education, in addition to clear cut legislation in order to avoid private interests abusing the power of social platforms. Citizens’ media literacy, as well as critical thinking, represents the first line of defence against disinformation and misinformation. NATO can provide some critical outreach activities in order to better prepare media, students in selected faculties and possibly wider publics against present and future manipulations.

Federico Berger

Junior Fellow at the NATO Defense College Foundation since 2020. BA graduate in International Relations, MA student in Public and Political Communication at the University of Turin. He is currently enrolled in the 360/Digital Sherlocks fellowship programme of the Atlantic Council’s DFRLab.