Arab rising and beyond

Claire Spencer

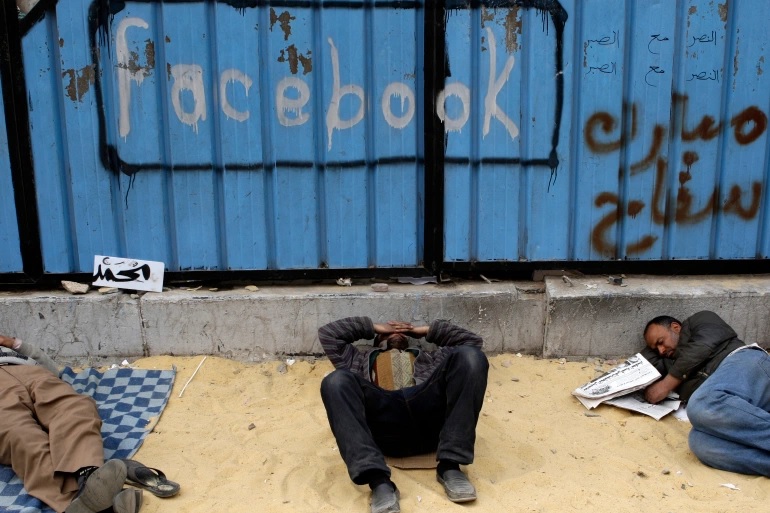

The uneven results of the 2011 and subsequent uprisings across the Arab world have been mainly registered at the political and strategic levels (whether through régime conservation, change, implosion or civil war), but the deepest changes have happened at the social level, very much like the 1968 revolts. Few of the protestors remain engaged in politics but the failure of existing governance structures and leaderships to connect with their societies has left a legacy of individual and collective self-reliance that was neither widespread nor apparent before 2011. It means that a radical shift in perceptions has moved Arab societies from seeing their governments as ultimate providers to being enablers, at best, or obstacles at worst to creating the eco-systems for the socio-economic transformations already underway. Will governments understand their new role in order to keep social and political peace? Perhaps only four countries in the 22 of the Arab League show some understanding of this predicament.

Over the next decade, change is also less likely to be driven by the street, as by the disruptive effects of new technologies, culture, innovation and new business models, all of which will impact the macro-economic climate, and hence politics of the post-global pandemic world.

The rapid decline of hydrocarbons in favour of renewable sources of energy will also disproportionately impact the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) in ways few of the region’s leaderships are prepared for. The most ambitious critics of linear projections foresee radical changes taking place within a matter of years. The authors of the RethinkX report “Rethinking Humanity” of June 2020 summarise their thinking as follows: “The five foundational sectors [information, energy, food, transportation, and materials], which gave rise to Western dominance starting with Europe in the 1500s and America in the 1900s, will all collapse during the 2020s. These sector disruptions are bookends to a civilization that birthed the Industrial Order, which both built the modern world and destroyed the rest. Furthermore, we are experiencing rising inequality, extremism, and populism, the deterioration of decision-making processes and the undermining of representative democracy, the accumulation of financial instability as we mortgage the future to pay for the present, ecological degradation, and climate change – all signs that our civilization has reached and breached its limits. The response from today’s incumbents to these challenges – more centralization, more extraction, more exploitation, more compromise of public health and environmental integrity in the name of competitive advantage and growth – is no less desperate than the response from those of prior civilizations who called for more walls, more priests, and more blood sacrifices as they faced collapse”(1).

This vision – of widespread and disruptive contests over power and the failure as well as inability of governments to respond to the expectations of their citizens – is echoed in the more prosaic language of the US Office of the Director of National Intelligence’s 4-yearly projection “Global Trends 2040”(2) .

Timeframes may differ, but no one doubts we are entering an age of acute instability. Thus, the spread of violence in the MENA cannot be discounted, nor, given the volatility of the young demographic of the region can further street-level protests, new forms of extremism, populism, terrorism and the emergence of non-state actors be excluded. Of most immediate concern to security analysts are the biotechnology and cyber security threats that are already emerging as the downside of new and devolved technologies. For every advance in alternative food production and meat substitution through stem cell technologies foreseen by RethinkX and others, there are concerns about the ‘escape’ of new viruses and the deliberate spread of biological warfare enabled by emerging technologies (3) .

Cyber security also conflates a number of risks and threats, as summarised in a recent World Economic Forum agenda paper: “(t)he complexity of digitalization means that governments are fighting different battles – from “fake news” intended to influence elections to cyber-attacks on critical infrastructure. These include the recent wave of ransomware attacks on healthcare systems to the pervasive impact of a compromised provider of widely-adopted network management systems. Vital processes, such as the delivery of the vaccines in the months to come, may also be at risk” (4).

Despite what now appears to be increasing geopolitical fragmentation, the key to understanding the game changers for the MENA region is that individual responses to global connectivity are far more likely to determine what happens next than predictions of the demise of globalisation and the increasing isolation of the Arab world.

As a result, security analysts and policy-driven alliances such as NATO need to think beyond the more immediate challenges that Europe’s proximity to the MENA region serves to attract. More attention should be given to the ‘hidden hand’ of developments that, if encouraged, could ultimately structure more positive and enduring changes over the longer term. This might mean devising new and decentralised approaches to conflict resolution that are not so reliant on state and non-state actors who lack any incentive to act on their undertakings and commitments, as in Libya. It requires seeking out and engaging actors who have yet to emerge as leaders, across social and economic sectors and geographies that have yet to define themselves as being the economic and political hubs of the future. Above all, for NATO, it will require a much larger focus on identifying new ‘organizing systems-in-the making’ and seeking out the individuals who are driving positive change wherever they are.

New forms of public-private security partnerships may also become more common than in just Russia, with the blending of state intelligence and criminal hackers, for instance. It was a set of criminal ‘influencers’ who assisted the FBI to track and arrest 800 criminals in June 2021 in a worldwide operation that covertly used a mobile communications app that was believed undecipherable by its users (5) .

Expecting the unexpected and proactively seeking out the most unlikely of security partners is critical to grasping what the longer-term outcomes of 2011 may yet bring to MENA and beyond(6).

(1) James Arbib and Tony Seba ‘Rethinking Humanity’/ June 2020

https://tonyseba.com/wpcontent/uploads/2020/09/RethinkXHumanityReport.pdf

(2) US Office of the Director of National Intelligence ‘Global Trends 2040: A More Contested World’ March 2021

https://www.dni.gov/index.php/gt2040-home/emerging-dynamics/state-dynamics

(3) See, for example, Kathleen M. Vogel and Sonia Ben Ouagrham-Gormley, ‘Anticipating emerging biotechnology threats’

Politics and the Life Sciences, Fall 2018, Vol 37, No. 2

https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/politics-and-the-life-sciences/article/anticipating-emerging-biotechnology-threats/ CCBB40DBD2BCE6CECDE9F2ACB71588CE

(4) World Economic Forum 2021, Davos Agenda ‘These are the top cybersecurity challenges of 2021’

https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2021/01/top-cybersecurity-challenges-of-2021/

(5) BBC News ‘ANOM: Hundreds arrested in massive global crime sting using messaging app’

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-57394831

(6) For a fuller version of these arguments, see Claire Spencer ‘Arab risings and beyond’ NATO Defense College Foundation Paper, June 2021

https://www.natofoundation.org/wpcontent/uploads/2021/06/NDCF-Paper-Spencer-Arab-risings-and-beyond.pdf

Claire Spencer

Dr Spencer is currently an independent consultant with the British Council working on the Hammamet series of conferences that fosters greater links between the UK and North Africa. She is a member of a number of advisory boards and associations relating to the MENA region. Dr Spencer is a Fellow of the Royal Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce.

Other articles

Foreword

Alessandro Minuto-Rizzo

Political Summary

Alessandro Politi

Policy Paper

Arab rising and beyond

Claire Spencer

The economy and the civil society

Possible roots of the rising

Abdulaziz Sager

What kind of economic prospects for the region?

Karim El Aynaoui, Oumayma Bourhriba

From the web to the square

Mahboub E. Hasem

Power and identity

10 Years After the Arab Spring: llicit Economies Evolve, Epand and Entrench

Matt Herbert

Libya: a multi-layer conflict

Umberto Profazio

The Egyptian long pacification

Eman Ragab

A new wave of unrest: towards change?

Future perspectives in the Gulf

Jean-Loup Saman

The way ahead

A look the the future

Ahmad Masa’deh

The Alliance looks South

Appendix

The Arab rising by country

Mahboub E. Hashem