Possible roots of the rising

Abdulaziz Sager

At the onset of the Arab Spring and in its aftermath over the last decade, the popular narrative regarding its causes has tended to focus primarily, if not exclusively, on a lack of growth and/or income inequality in the countries where the popular uprisings occurred. However, empirical data on growth across the region in the years leading up to 2011 suggest otherwise. In fact, many countries in the region experienced a decade or more of rapid growth before 2010 and even at the time of the uprisings (including Egypt, Tunisia, Lebanon, Jordan, Libya and Yemen), experienced more than 5% of real growth(1). Therefore, the cause of the uprisings could not have been due to a simple lack of growth.

Others have suggested that the cause was more likely due to inadequate income distribution or wealth inequality playing a primary role in fostering the socio-economic conditions that led to the uprisings. Nonetheless, as economic growth was increasing in the region in the years leading to the Arab Spring, empirical data demonstrates that income inequality was decreasing, disproving this hypothesis. According to World Bank data, the Gini coefficient, used to measure wealth inequality, fell in Egypt from 36,1% in 2000 to 30,7% in 2009(2), which represents a very low figure by regional and international standards. It would be therefore inaccurate to outline the causes of the Arab Spring simply in terms of growth or income distribution within the individual countries that experienced uprisings and/or unrest at the time. A more complete picture should take into account not only the measure of inequality at the country level but also the regional level, which is consistent with the fact that the Arab Spring was itself was regional phenomenon.

At the regional level (and in comparison, with other regions globally), income inequality is extremely high at the top of the MENA as a whole. The share of total income in the region accruing to the top 10% income receivers is currently 55% (versus 48% in the US, 36% in Western Europe, and 54% in South Africa)(3). The top 1% share might exceed 25% (versus 20% in the US, 11% in Western Europe, and 17% in South Africa). It is also important to consider that it was not necessarily a “growth” in inequality per se that led to the uprisings, but perhaps instead a shift towards increasing intolerance towards already existing levels of inequality and cronyism, which speaks more to the idea of values and aspirations representing a catalyst of the Arab Spring.

That is to say that popular perceptions about corruption and cronyism are equally important when considering the causes of the Arab Spring uprisings, and not just the empirical levels of corruption and cronyism. Nevertheless, data indeed indicate that corruption in the MENA had been on the rise prior to 2011 and that in some respects the MENA appears to stand out for having more corruption than other regions comprising developing countries, and much higher corruption levels than the world average in general(4). With regard to cronyism in the MENA in particular, unlike other regions within Asia that have witnessed cronyism, the major negative consequences stem from a lack of competent and efficient cronies, a mechanism to weed out non-performing cronies, and the fact that countries in the region have been unsuccessful in steering the cronies’ appetite for profit in a direction that would serve their countries’ development strategies.

The World Bank shed light on this phenomenon of cronyism in the region, and in particular in the case of Tunisia(5) in its 2014 report, “The unfin ished revolution: bringing opportunity, good jobs and greater wealth to all Tunisians,” in which the World Bank emphasizes that cronyism in Tunisia existed long before Ben Ali’s rise to power, while remaining an ongoing obstacle to Tunisia’s growth as a constant characteristic of its economy. A later World Bank report elaborates on this analysis of cronyism in the region, while focusing primarily on Egypt and Yemen and the ways that political connectedness relate to economic success in those countries(6). According to the report, in the case of Egypt, politically connected firms accounted for 60% of profits of medium and large firms, including privileges ranging from protection granted through non-tariff barriers, preferential access to land and credit, and privileged access to the state bureaucracy and permits.

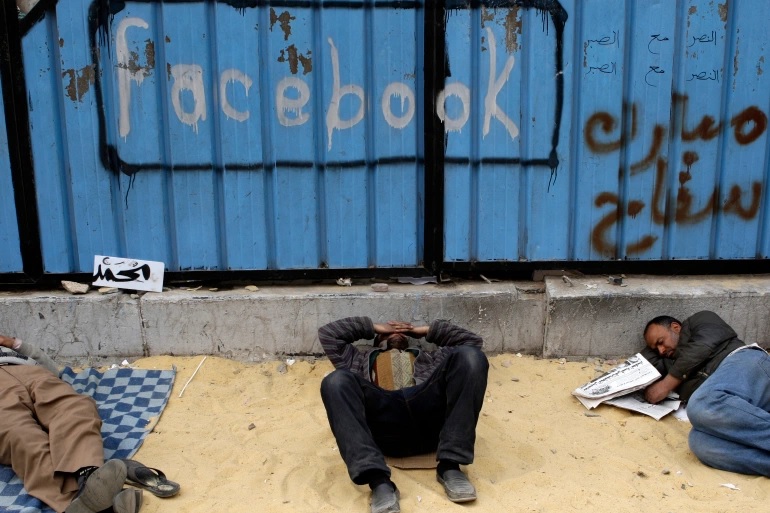

Finally, it is important to bear in mind that unemployment during the period prior to the Arab Spring was exacerbated and it was primarily the connected that benefited from employment opportunities. In this context, a stratum of middle-class professionals and small and medium entrepreneurs found themselves relatively marginalized and probably more aware of the concentration of wealth and profits in the hands of small cliques tied to political power. Therefore, it is notably this middle class that might have made the difference in igniting the chain of uprisings across the region, considering that it is indeed the middle class that possesses and is competent in the tools of modern communications technologies. These technologies, and especially social media, allowed discontented groups to connect to the wider masses in a relatively short period of time, which proved vital in organizing the uprisings and drawing support and attention to them on a local, regional and international scale.

(1) Ghanem, H. (2015). The Arab spring five years later, volume 1: Toward great inclusiveness (p. 39-40). Washington, D.C., DC: Brookings Institution.

(2) Gini index (World Bank estimate) – Egypt, Arab Rep. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/ SI.POV.GINI?end=2017&locations=EG&start=1990&view=chart.

(3) Alvaredo, Facundo & Piketty, Thomas, 2014. “Measuring Top Incomes and lnequality in the Middle East: Data Limitations and Illustration with the Case of Egypt,” CEPR Discussion Papers 10068, C.E.P.R. Discussion Papers.

(4) Ianchovichina, Elena. 2018. Eruptions of Popular Anger: The Economics of the Arab Spring and Its Aftermath (pages 93-107). MENA Development Report; Washington, DC: World Bank. © World Bank. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/28961 License: CC BY 3.0 IGO.

(5) The unfinished revolution: bringing opportunity, good jobs and greater wealth to all Tunisians (English). Washington, D.C.: World Bank Group. (Chapter 3 ‘Cronyism, Economic Performance and Unequal Opportunity’) http://documents.worldbank.org/ curated/en/658461468312323813/The-unfinished-revolution-bringing-opportunity-good-jobs-and-greater-wealth-to-all-Tunisians

(6) Schiffbauer, Marc, Abdoulaye Sy, Sahar Hussain, Hania Sahnoun, and Philip Keefer. 2015. Jobs or Privileges: Unleashing the Employment Potential of the Middle East and North Africa. Washington, DC: World Bank. doi: 10.1596/978-1-4648-0405-2. License: Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 3.0 IGO (Chapter 4 ‘Privileges, competition and job creation’).

Abdulaziz Sager

A Saudi expert on Gulf politics and strategic issues, Dr Sager is the founder and Chairman of the Gulf Research Center (GRC), a global think tank based in Jeddah with a well-established worldwide network. He frequently contributes as a commentator on major international media channels such as Al Arabiya, France 24 and BBC.

Other articles

Foreword

Alessandro Minuto-Rizzo

Political Summary

Alessandro Politi

Policy Paper

Arab rising and beyond

Claire Spencer

The economy and the civil society

Possible roots of the rising

Abdulaziz Sager

What kind of economic prospects for the region?

Karim El Aynaoui, Oumayma Bourhriba

From the web to the square

Mahboub E. Hasem

Power and identity

10 Years After the Arab Spring: llicit Economies Evolve, Epand and Entrench

Matt Herbert

Libya: a multi-layer conflict

Umberto Profazio

The Egyptian long pacification

Eman Ragab

A new wave of unrest: towards change?

Future perspectives in the Gulf

Jean-Loup Saman

The way ahead

A look the the future

Ahmad Masa’deh

The Alliance looks South

Appendix

The Arab rising by country

Mahboub E. Hashem