The Algerians between the “pouvoir” and the “revolution of smiles”

Brahim Oumansour

Since February 22, 2019, Algeria has been shaken by a nationwide protest movement termed Hirak (Arabic for movement), also called “Revolution of smiles” because of its peaceful nature. The Hirak (Movement) mobilised first against former president Abdelaziz Bouteflika’s bid for a fifth term, despite his age and ailing health. The movement continued demanding radical regime change and the departure of the ruling elite, as well as a transition toward democracy and the rule of law.

The protest movement surprised the international community and observers of Algerian politics, as the country had largely avoided the mass rallies held across the Middle East and North Africa during the socalled Arab Spring in 2011. Algeria today faces multifaceted challenges, as thousands of people continue to protest against the military-backed president, Abdelmadjid Tebboune, elected on the 12th of December 2019, amidst an economic and social crisis that has worsened due to the fall of oil prices and the pandemic, forcing the government to cut the budget by 50%1 . Algeria is at a crossroads between stability through authoritarianism or through democratization and deep political reforms.

In 2011, Algeria survived the shockwave of the Arab revolts that broke out in Tunisia then spread to the whole region, resulting in the downfall of governments in Tunisia, Egypt, Libya and Yemen. At that time, Algerians refrained from going massively into the streets for several reasons. First, Bouteflika had been credited with bringing back peace after a bloody decade of terrorism, presenting himself as the man who brought stability to the country. Then, he and his entourage succeeded in establishing a solid circle including the Front de Liberation National (FLN) and the military: two pillars of the Algerian political system. Moreover, high oil revenues allowed the regime to promote stability and co-opt certain opposition groups through cronyism and heavy social spending, accompanied by a set of political reforms such as ending the state of emergency. Bouteflika also promised huge investments and extended social programmes. Finally, his regime combined the clientelist distribution of wealth with repressive measures to thwart demonstrations of those who tried to break the curtain of fear during his four-term rule.

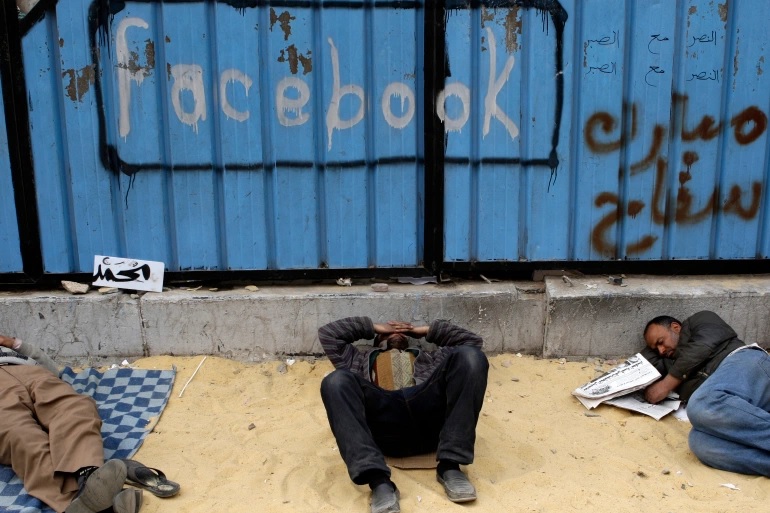

The Hirak is the outcome of years of growing dissatisfaction toward an outdated system that failed carry out efficient structural reforms to lead the country towards a more productive economy and inclusive political system of governance, endowed with the capacity to tackle the longstanding issues of unemployment, political and economic stagnation. Hundreds of thousands of Algerians march every Friday sharing almost the same political slogans and demands across the country. The leaderless peaceful movement emerged outside the traditional opposition parties. Political maturity among a growing middle-class and more educated youth helped the advent of this new form of protest. The Internet and social media in particular, which are now more available across Algeria, have also contributed to the spread of the protests, helping to broadcast and coordinate actions in different cities.

Despite its radical demands and the regime’s repression, the protesters maintain peaceful marches. There is shared consciousness among both the population and policymakers about the risks of violent protest or violent clashes between the protesters and security forces. Many Algerians are still cognizant of the bloody experience of the 1990s or the drifts of the Arab spring in neighbouring states, like Libya and Syria.

Under pressure, decision-makers have introduced limited change by setting up the National Independent Authority for Elections, organizing a presidential election on December 12, 2019 which saw a historically low turnout of 40%2. The newly elected president Tebboune formed a new government and called for a referendum on revision of the Constitution. At the same time, security forces have conducted a purge, arresting high profile, dishonest businessmen (the so-called Oligarchs) and political personalities as well as high-ranking corrupt military officers close to Bouteflika’s inner circle.

However, the Hirak continues its opposition to the authoritarian regime, considering the roadmap of the decision-makers insufficient, asking instead for radical reforms and the establishment of a genuine democratic system. The offer of the government is not much different from what previous governments did. After being suspended for months at the outbreak of the Covid-19, the weekly marches have returned despite the pandemic. The unplanned fall of Bouteflika brought the military to the frontline. Repressive policy against some journalists and activists has deepened the crisis of confidence between the citizens and the ruling elite; this is illustrated in the attacks levelled against the authorities for their slow response to the Covid-19 pandemic.

The standoff between the protesters and Algerian authorities continues over early parliamentary elections scheduled on June 12, largely rejected by Hirak activists and some opposition parties, amid growing economic and social predicaments that resulted from poor governance, corruption and cronyism. Financial reserves are being depleted to compensate for the drop in oil prices. In addition, the historical legitimacy of the old rulers is no longer convincing. Actually, protesters themselves use the symbols of the war for Independence as means to delegitimize the ruling elite.

The current situation could lead to two different scenarios. Either Algeria returns to an effective authoritarian regime in response to concerns over social unrest and regional tensions and instability, renewing mechanisms of allegiance while keeping a facade democracy. Or concerns over social unrest could entice authorities to agree on a negotiated democratic transition. The current situation is reminiscent of the botched democratic transition of 1989 which resulted from the collapse in oil prices in 1986 that paved the way to the 1988 riots. In fact, Algeria has already experienced an “Arab Spring” revolt in October, with the outbreak of mass protests turned into riots, resulting in an abrupt end of a one-party system rule.

Consequently, Algeria adopted a new Constitution, in 1989, including several liberalizing laws and the institutionalization of political pluralism and freedom of the press. But the process was cut short when the military abolished the second round of legislative elections with the prospect of an Islamist takeover by the Islamic Salvation Front (FIS), which paved the way for the bloody decade and a return to authoritarianism, toughened by the establishment of a lasting state of emergency3.

In sum, Algeria is currently facing a political deadlock. Decision-makers offer only limited changes and offer no serious dialogue with the protesters. On the Hirak side, protesters keep contesting the legitimacy of the new government and refrain from forming a leadership to prevent the regime from co-opting the movement. Besides, Algeria missed the opportunity to diversify its economy and carry out structural reforms during the prices boom to reduce its dependence on hydrocarbon exports. Today, the government should handle the political crisis to tackle economic and social issues, as it is hard to dissociate the economy from political problems. There is need for effective transition to a more democratic system and the institution of good governance. A transparent and inclusive political system is essential to renew trust, boost creativity and attract local and foreign investments, in addition to structural reforms within the financial system.

1) Ould Ahmed, Hamid, « Algeria announces a new cut in 2020 public spending », Reuters, May 4, 2020. Link: https://www.reuters.com/article/ozabs-us-algeria-economy-idAFKBN22G0QS-OZABS

2) 2 APS, «Presidential election: Overall voter turnout 39,83%», December 13, 2019. Link: https://www.aps.dz/en/algeria/32262-presidential-election-overall-voter-turnout-39-33

3) Zoubir, Yahia, «The Algerian Crisis: Origins and Prospects for a ‘Second Republic’» (report), Al Jazeera Center for Studies, 2016.

Brahim Oumansour

A consultant in geopolitics and global strategy, Dr Oumansour is an Associate Research Fellow at the Center for Arab and Mediterranean Studies and Research and at the French Institute for International and Strategic Affairs where he currently lectures as an expert in global strategy at the Sup’ Master degrees in Defence, Security and Crisis Management, and in Geopolitics and Prospective. He also lectures in Comparing Political Systems at Université Paris-Est Créteil.

Other articles

Foreword

Alessandro Minuto-Rizzo

Political Summary

Alessandro Politi

Policy Paper

Arab rising and beyond

Claire Spencer

The economy and the civil society

Possible roots of the rising

Abdulaziz Sager

What kind of economic prospects for the region?

Karim El Aynaoui, Oumayma Bourhriba

From the web to the square

Mahboub E. Hasem

Power and identity

10 Years After the Arab Spring: llicit Economies Evolve, Epand and Entrench

Matt Herbert

Libya: a multi-layer conflict

Umberto Profazio

The Egyptian long pacification

Eman Ragab

A new wave of unrest: towards change?

Future perspectives in the Gulf

Jean-Loup Saman

The way ahead

A look the the future

Ahmad Masa’deh

The Alliance looks South

Appendix

The Arab rising by country

Mahboub E. Hashem