From the web to the square

Mahboub E. Hasem

The 2011 risings have marked significantly the region, not just in terms of narrative, but of concrete political, social and economic dislocation. From a strategic point of view, it is important to focus more clearly than in the past about the causes and effects of these momentous events. Five are then the main causes and six the most important effects. More detailed country analyses are available in the appendix.

The five causes

Widespread Corruption: corruption remains pervasive in the MENA region, which has been stricken by conflicts, dictatorships, and increasing attacks on freedom of expression, press autonomy, and civil society. Economic hardships cannot be tolerated when people cannot foresee a better future ahead, feel that there is adequate distribution of wealth, and are beset by painful conditions to say the least. Any kind of development that takes place in the Arab states leads to crony capitalism, nepotism, favouritism, and despotism, which benefit only a small minority of associates, relatives, and friends. Business elites cooperate with their regimes to accumulate treasures incredible to the common people living on little to no money per day. In those countries, no business pact is closed without a kick-back to the governing entity and immediate family. Finally, although some meek attempts towards fighting corruption and increasing transparency have been made in a few Arab states, the scale of these endeavours remains abysmal.

Fundamentally, demonstrators were encouraged by an aspiration for dignity and human rights, even though spiritual tensions also played a major role. Such as was the case with Islamist parties and the Muslim Brotherhood who got power in formerly secular Tunisia and for a shortterm in Egypt, when Mohammad Morsi was voted into presidential power. Similarly, profound spiritual divisions gave rise to the anti-government movement in Bahrain, Syria, and Yemen early on and is still ongoing.

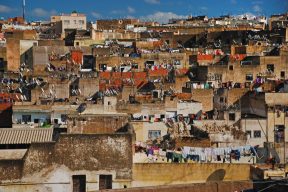

Unemployment: youth unemployment has been a ticking bomb for many years in the MENA region. Rates of joblessness among an increasing Arab youth population has been stagnant because Arab authorities and their economic policies simply cannot keep up with the shocking increase in their populations. For instance, Lebanese educated youths migrate to work abroad, due to inability of finding decent jobs in their homeland; two-thirds of Egyptians are under the age of 30 and rates of unemployment are skyrocketing. Furthermore, the standards of living have been deteriorating and have been inspiring people to continue rebelling. Besides, Arabs have a prolonged saga of struggle for radical change, from leftist groups, Islamist, fanatics, terrorists to extremists. Nevertheless, the uprisings of 2011 and again in 2018-2021 could not have grown into an extensive confrontation, had it not been for the prevalent dissatisfaction over unemployment, poverty, and low living standards. Families struggling to provide for their kids have surpassed moral disputes in order to rebel for the purpose of changing the status quo/business as usual governance.

Old Rulers and Transferring Power to their Children: a considerable number of Arab leaders have been old, besides being corrupt. When Arab Springs occurred in 2011, the Egyptian leader, Hosni Mubarak, had been in power for 30 years; Tunisia’s Ben Ali, 24 years; Muammar al-Qaddafi, 42 years; Ali Saleh, 22 years; and Omar Al-Bashir, 30 years. In Lebanon, the Zaeem (godfather) system has been a crooked patronage structure wherein a few political bosses manipulate elections and allocate political favours and financial rewards to those close to them. They also manage to transfer power to their heirs before they are deceased. Also, Lebanese parliamentarians usually serve the needs of local sector clientele and neglect nationwide concerns. In addition, demonstrators had not been backed by any particular groups or leaders anywhere, especially in the Lebanese uprising (17/10/2019). Instead, they had been acting primarily on the spurof-the-moment, which made it difficult for authorities to prevent any protest movement by simply arresting a few agitators, a situation that regime forces were entirely unprepared for. Therefore, politicians are the worst enemies of their own people and it is extremely hard to consider how to remove them soon without a miracle.

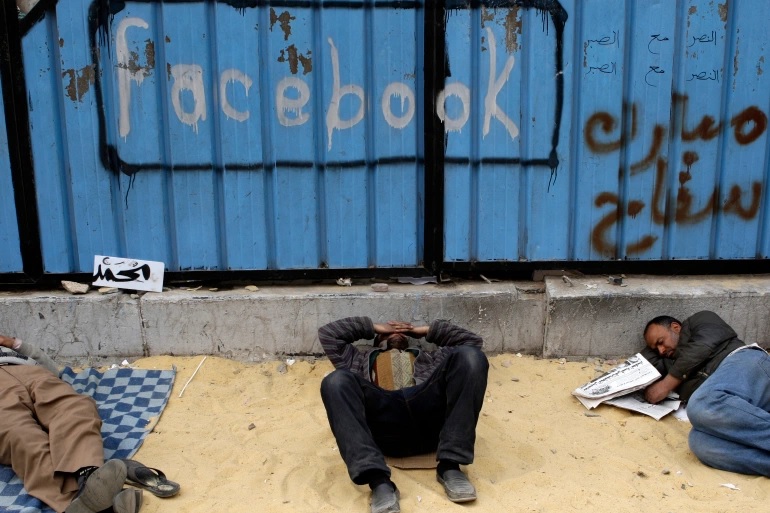

Social Media: mass protests were revealed on social media by anonymous activists, who managed to successfully appeal to many people in order to gather in “Tahrir” squares. Social media, back then, proved to be powerful mobilization tools that aided activists to outsmart the police forces. Besides the squares, mosques could serve as starting points for rallying or assembling, especially on Fridays, after the weekly address and prayers. Hence, activists could march down in huge rallies to squares against their dictators. Arab authorities, that could block off squares and target universities, could not close down the mosques of the country. Thus, they were unable to control huge public demonstrations.

Authorities Reaction: Arab dictators’ reaction to the demonstrations was definitely dreadful, going from expulsion to horror, from police force cruelty to random change that came too little too late; and efforts to quell demonstrations using force failed dramatically. All burials of regime’s viciousness victims only intensified the rage and moved more people to the streets to protest Besides, the revolt has been contagious and has spread quickly from one Arab state to another. Riots are nevertheless ongoing, even though with less intensity due mainly to the Coronavirus pandemic. In Libya, Yemen, and Syria, those protests and efforts led to civil wars that are still continuing.

The six effects

Democracy: Only Tunisia appears to have made an enduring shift to a superficial democracy, although it is still experiencing some street troubles. Egypt, after a short period of democratic elections which elected Mohammad Morsi as president, reverted back to another repressive regime of Abdel Fattah Al-Sisi, who is still in power and whose regime led to detain many journalists in the region. His rule is portrayed as harder than that of Hosni Mubarak; conversely, Libya, Syria, and Yemen spiralled into prolonged civil wars which are persistent. While Syrian President Bashar Al-Assad is still in power, due to Russian and Iranian military direct intervention, Omar al-Bashir is in prison, but Libyan Kaddafi and Yemen Ali Saleh were assassinated.

Freedom: democracy and freedom are sine qua non to one another, they are like the two faces of a coin. The failure of democratization is a direct result of the ultimate power of Arab states that reject democratic transition by any means: a transition that can only accomplished when the states’ coercive power is diminished and the leaders don’t have the will to crush their adversaries. Many states in the region have been until now very capable to quash any reform or modernization, destroying any challenger. Therefore, there is now much less press freedom, with authorities targeting systematically journalists.

Mass Displacement: Another typical result of the uprisings and the civil wars which ensued in Libya, Syria, and Yemen was the mass displacement of citizenries. For instance, Syria’s war alone pushed more than twelve million refugees and internally displaced citizens into surrounding countries (Turkey, Jordan, and Lebanon) and beyond.

Stifling Freedom of Internet and Social Media Usage: These have been dynamic tools for rallying protestors and, without them, all demonstrations would have been quickly beaten. Authorities have restricted access though draconian censorship laws and imprisonment for any anti-regime posting. Only Tunisia has enhanced internet freedom, mainly by defending free expression within its 2014 constitution and by protecting whistle-blowers denouncing corrupt people with mixed results, not to speak about the rest of the region.

Gender equality: due to women assuming leading roles in rallies, albeit the menace of gender-based violence, some gender equality was achieved. Over the past ten years, several Arab nations have witnessed unimportant upturns in female representation in authority, but mostly the region has done little to advance the standing of women. Nevertheless, women today are voicing their opinions and speaking out more against injustices they face. Besides, some women were appointed into ministerial positions, namely in the United Arab Emirates and Lebanon, something unseen before.

Poverty: poverty rates have been exceptionally high in MENA. Since the year 2011, stark poverty in MENA has virtually doubled, rising from about 3% of the populace to nearly 5%; and an estimated 19 million people in the region are living on less than $2,0 per day. MENA’s poverty indicators comprise, lack of proper education, poor health, standard of living and diffused violence. Once people fall into poverty, they are increasingly likely to remain poor for a long time and with very few assets, if any, to pull themselves out of it.

Research findings suggest that MENA is the among the most iniquitous regions in the world. Already region, the top 10% of the population holds 61% of the wealth, compared to 47% in the United States and 36% in Western Europe, but the worst is that poverty was increased by conflicts (especially in Syria and Yemen) and sanctions.

A line on the bottom

Events like these, exactly like other uprisings or revolutions in the past, require a rolling judgement as time unfurls less evident consequences. Today populations pay a heavy price in too many failed states, in addition to long stonewalled reforms, while meek and spotty progress on economy, gender equality, political reforms and social development in very few cases was made. Despite horrendous repression, similarly to what happened also during the Cold War, the spirit of the revolts is far from over, as evidenced by the second wave of uprisings that caughton in Sudan, Algeria, Iraq and Lebanon eight years later. The demands are tenaciously the same: transparency, end to corruption, democratic reforms. Authoritarian regimes have also had their learning process in the ensuing “Arab Winters”: thanks to unscrupulous Western firms and stalwart assistance from similar regime, they mastered the cyberspace to monitor, repress, disinform. For how long?

Mahboub E. Hashem

Dr Mahboub E. Hashem is currently a private consultant on entrepreneurial and groundbreaking industries as well as professional communication practices based in the City of Toledo, Ohio, United States of America. Hitherto, he served as professor, founder and former head of the Mass Communication Department at the American University of Sharjah (AUS), where he also chaired the Department of English, Mass Communication, and Translation. Besides, Dr. Hashem founded the Global Media Journal- Arabian Edition (GMJ-AE), serving as Executive Editor from 2009 to 2014. Author of several thematic research, he has been a leading consultant on establishing communication programs for many educational institutions worldwide.

Other articles

Foreword

Alessandro Minuto-Rizzo

Political Summary

Alessandro Politi

Policy Paper

Arab rising and beyond

Claire Spencer

The economy and the civil society

Possible roots of the rising

Abdulaziz Sager

What kind of economic prospects for the region?

Karim El Aynaoui, Oumayma Bourhriba

From the web to the square

Mahboub E. Hasem

Power and identity

10 Years After the Arab Spring: llicit Economies Evolve, Epand and Entrench

Matt Herbert

Libya: a multi-layer conflict

Umberto Profazio

The Egyptian long pacification

Eman Ragab

A new wave of unrest: towards change?

Future perspectives in the Gulf

Jean-Loup Saman

The way ahead

A look the the future

Ahmad Masa’deh

The Alliance looks South

Appendix

The Arab rising by country

Mahboub E. Hashem